“While they were there, the time came for the baby to be born,

and she gave birth to her firstborn, a son.”

Luke 2:6 (NIV)

In an unknown town, a week’s distance from the womanly wisdom of mother, sisters, aunts, it began. Plodding heavily beside her faithful betrothed along strange and bustling streets, filthy and rapidly darkening streets, a distinct tightening and quick intake of breath. The same quiet centering swell that had been slowly intensifying since before dawn was mounting again as they turned to climb the slight rise of a narrow and mud-blotched side street.

She stops for a moment to collect herself and he turns to meet her knowing eyes. “Surely not now?” his silent gaze seems to ask, a flicker of panic flaring from behind those steady dark irises. “Let’s try this place at the end of the road,” he suggests, “Maybe they have a place where you can rest.”

Nativity, Unknown Master (Slovakia c.1490)

What could it have been like, might it have been like, for Mary on the eve of Christ’s birth? For some Catholics his birth was as miraculous as his conception, a painless event that retained the young maiden’s perpetual virginity and fulfills the prophet Isaiah’s declaration about the city of Zion in Isaiah 66:7:

“Before she was in labor she gave birth; before her pain came upon her she delivered a son.

Who has heard such a thing? Who has seen such things?”

It is possible. After all, what isn’t wholly miraculous and nature-defying about a child who is fully human and fully divine? What isn’t curious and mind-bending about angels appearing in a night sky and philosophers spontaneously trekking after a never-before-seen star? What is far-fetched about a loving God intervening to reverse a curse? If the God of heaven and earth wants to supersede the biological and physiological processes that govern labor He surely can. But it seems worthwhile to wonder: Did he?

Protestant Christians, on the other hand, are decidedly disinclined to wonder at such things. Crisp white linens and a rosy-cheeked Mary do just fine for most believers from my tradition, which often struggles to view the body as anything more than a tainted sin vessel, the virgin mother as anything more than a dangerous idol.

For both traditions, thinking about a virginal young woman crouching low on a dirt floor with sweat-matted hair, bleeding and breathing in soft cries and earthy groans as she harnesses strength to push her baby down, does not easily align with tidy views of a holy birth. Yet given what we know of the ancient near East, of women’s bodies and births in every age, of God and his consistency, it seems equally possible that a son born of water and blood, pushed and pressed through the dual forces of love and pain, may have been very much the point of Christ’s delivery.

Water and blood are elements that pulse with significance through all of Scripture. They are the elements and symbols that Catholics and Protestants share sacramentally in Baptism and Communion. They are also both prevalent in the natural course of labor and delivery in ways that powerfully echo and foreshadow the grand logic of creation and redemption.

In her book, Eve’s Revenge: A Spirituality of the Body for Women, Lilian Calles Barger emphasizes the redemptive thread that winds through the womb, noting that while Eve is often stereotyped as a wicked seductress and Mary upheld as the perfect, unpolluted mother, in fact:

Neither of these [culturally-laden] stereotypes can be derived from the biblical text. Instead Mary of Nazareth is the true daughter of Eve who lives out God’s promise to her mother by giving birth to her own Redeemer. As Eve came from the first Adam, Jesus, who is called the second Adam, now comes from the woman. As humanity was created in the image of God, Jesus is said to be the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of the new creation (Col 1:15).

This image of Mary “giving birth to her own Redeemer” is a powerful one. In The Divine Comedy Dante leans on this paradox when he has Bernard of Clairvaux address her as “figlia del tuo figlio,” or “daughter of thy son”. Likewise, as Malcolm Guite points out in his beautiful Advent book, Waiting on the Word, John Donne, in his poem, “Ascension”, addresses Mary similarly saying, “yea, thou art now/Thy Maker’s maker, and thy Father’s mother.”

In all of these allusions we feel the sense of an honored feminine presence, a tender and elevated maternal concept, but to really consider what it means that Mary delivered her Deliverer raises a different set of questions entirely. It insists that we contend with what deliverance means and what it requires, at birth or otherwise.

And here is where the water and blood come in.

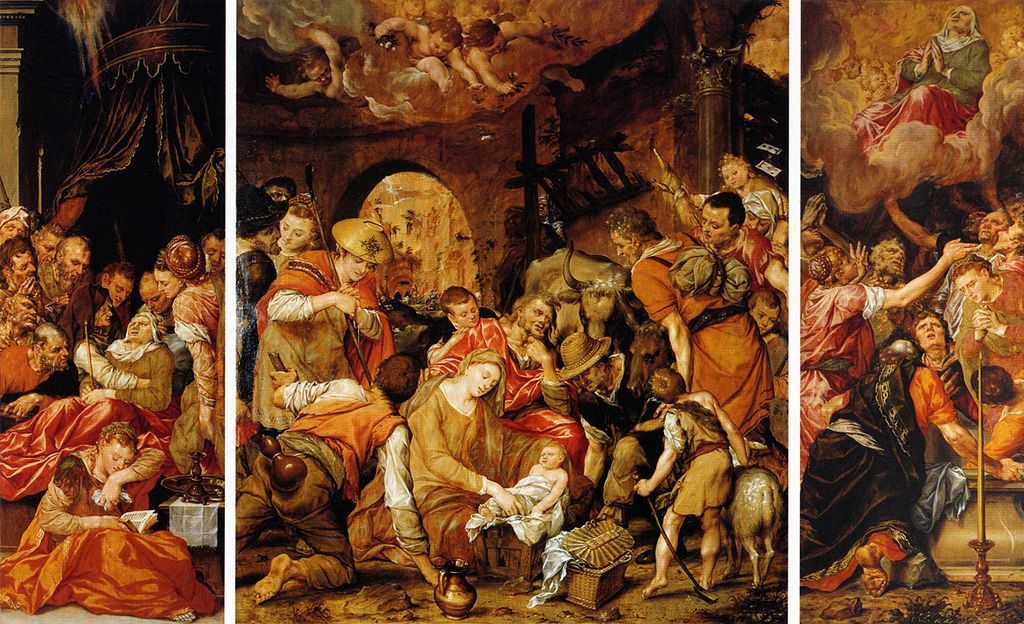

Triptych with the Life of Mary, Dirck Barendsz (1565)

God’s promises and acts of deliverance throughout Scripture and history never come cheap or easy: there is always the cost of blood, there is always the power of water, there is always a long endurance through fear and uncertainty that those being delivered must willingly embrace.

When God delivers Noah from the savage but cleansing waters of the flood it comes at the cost, the blood, of all creation dying. Meanwhile, Noah himself endures 40 days in a confined boat with the Wild Kingdom, likely pondering how to rebuild a new life in a now stricken and barren land.

Later, when God delivered Israel out of Egypt it came at the cost of every Egyptian’s firstborn son: a lamb’s blood on the lintel their only salvation from a child’s blood on the floor. Soon after, the heavy waters of the Red Sea brought cleansing to Israel by drowning their enemies and a tenuous 40-year trek through the desert ensued. In body and flesh they were delivered. By blood and by water they were delivered.

Much later, Christ’s own ministry is estimated to have lasted 3 years, or approximately 40 months, during which time many were delivered of physical ailments, evil spirits, and doubt. Every time, deliverance is extended to those who are willing to both release and receive, to give up something that binds them — often with great difficulty — and to accept something unknown with the promise of freedom. “Do you want to be well?” he asks the lame man at the pool of healing in John 5:6. “Go sell all of your possessions” he directs the rich ruler in Matthew 19:21. Deliverance demands that we be willing to make physical, material, and bodily risks as well as spiritual and emotional ones. For Christ, too, deliverance came by water and blood: the sweat of his brow, the blood from his wounds, the co-mingled flow of both when a lance struck His lifeless side.

Given all of this consistent imagery, this elemental rhythm and pulse of water and blood and strain and flesh, should it surprise us that God’s redemption in Christ would begin with a 40-week gestational term? A term that was likely littered with honest questions and the normal physical strains of yielding to pregnancy. Should we be amazed or made uncomfortable by the idea that our Deliverer, The Deliverer, would be delivered to us through the very natural and arduous rush of blood and water at birth?

For anyone who has had the privilege to witness a healthy and natural birth, it seems the most likely and beautiful scenario of all.

Consider this passage from Marilynne Robinson’s Pulitzer-prize winning novel Gilead where the main character, Reverend Ames, watches a young couple walking on his way to church and reflects:

The sun had come up brilliantly after a heavy rain, and the trees were glistening and very wet. On some impulse, plain exuberance, I suppose, the fellow jumped up and caught hold of a branch, and a storm of luminous water came pouring down on the two of them, and they laughed and took off running, the girl sweeping water off her hair and her dress as if she were a little bit disgusted, but she wasn’t. It was a beautiful thing to see, like something from a myth. I don’t know why I thought of that now, except perhaps because it is easy to believe in such moments that water was made primarily for blessing, and only secondarily for growing vegetables or doing the wash. I wish I had paid more attention to it.

In moments of birth it is especially easy to believe that water was made primarily for blessing, a kind of elemental anointing that is bestowed freely and universally to each and every child upon their arrival. Take, for example, a woman’s “water breaking”, which typically signals a child’s imminent arrival and initiates the transition between a child “breathing” from the mother and breathing on his own. It thus serves as a kind of physiological baptism for both mother and child, marking the threshold between the inner and outer world, between a sheltered and cloistered life and a new, wilder one outside. Add to that the water of tears, the water of sweat, the water that transforms itself into nourishing milk, and it seems clear enough why baptism later invokes water as the sign of rebirth.

The bloodiness of birth, too, is a startling and vivid sign of what it costs to give life, and to bear it. Poems like Kevin Young’s “Crowning” capture the wonder and powerful embodiment of that blood and strain in a way that is nothing short of sacred witness. Consider this short excerpt:

Almost there, almost out,

Maybe never, animal smell,

And peat, breath and sweat

And mulch-matter, and at once

You descend, or drive, or are driven

By mother’s body, by her will

And brilliance, by bowel,

By wanting and your hair

Peering as if it could see, and I saw

You storming forth,

Taproot, your cap of hair half

In, half out, and wait, hold

it there, the doctors say, and

She squeezing my hand, her face

Full of fire, then groaning your face

Out like a flower, blood-bloom,

Crocused into air…

Be Be (The Nativity), Paul Gauguin (1896)

Can we bring ourselves to imagine that Joseph, alongside a host of veteran mares and ewes, were witnesses to this same wonder? Standing in deference, in awe, as this small and gentle girl-woman garners power and strength, “by her will/And brilliance, by bowel/ And wanting” to give her whole self to this child? To give herself to God in birth as an act of worship? What a powerful picture of redemption for Mary to labor with ardor and purpose under a promise of redemption when every other woman since Eve had suffered those same pains only under a curse.

For Mary, like any woman, to enter into childbirth was to assume a great risk. The very term “delivery” suggests the possibility of death. It conveys the reality that a mother and child will not necessarily be delivered from (that is, survive) the threatening ordeals of labor and birth. Sadly, not all do. For Mary, a first-time mother, entering into this threat all alone, in a strange and busy town far from her home, perhaps without the support of a familiar or skilled midwife, must have been utterly terrifying. And yet, she did it.

In this way, Mary’s faithful willingness to deliver Christ, in addition to the simple fact of Christ’s delivery, gives us a lens for understanding our own hopes for deliverance from pain, from suffering, from doubt, or bondage, or evil this Christmas season. In our desire to find freedom we must be willing to both release and receive as in birth. We must, like the lame man, be willing to give up the familiarity of our sickness in favor of an unknown, and possibly terrifying, healing. We must, like the rich ruler, ask if we are willing to unshackle ourselves from material comforts to be available for even better goods. And for most of us, like Mary, it will not come quick or easy. It will require labor and risk. Water and blood.

Like Mary we may be asked to keep taking small and quiet steps through early stages of discomfort, to keep moving deeper into our obedience despite a fearful unknowing. We might find ourselves crying out for support, begging for words of hope and encouragement, for a hand to clasp, when we grow overwhelmed or fretful. We must keep breathing.

In the climax of our pain and helplessness we must cling to Christ, our Deliverer, to help us as he helped Mary, Theotokos, the God-bearer. Who, not only invited and carried Christ into herself in meek obedience, but also surrendered herself to the quiet violence that it is required for bringing Christ and His love into the world for the sake of abiding joy.