Part of the focus in our “Doubt, Deconstruction & Redemption” Series this year has been to make space for faithful Christians to ask hard questions that deserve to be asked and thoughtfully answered. Two big types of questions both Christians and non-Christians often ask are:

Part of the focus in our “Doubt, Deconstruction & Redemption” Series this year has been to make space for faithful Christians to ask hard questions that deserve to be asked and thoughtfully answered. Two big types of questions both Christians and non-Christians often ask are:

“How does Christianity fit into a world full of other religions? Is Jesus really worth following amidst so many different religious founders through the centuries?”

And

“What is the relationship between science and faith? How do the scientific discoveries of the last 400 years resonate or clash with the claims of Christianity?”

Over the next two SOUNDINGS posts, we will be offering resources Bill has developed over the years to address those two questions.

Today, we are sharing a recording and transcript of an address Bill gave to a group of National Geographic staff in 2015 in Washington DC. He was delighted and honored to share his significant experiences with the major world religions through the years and why he still chose to follow Jesus at the end of his exploring. We hope you are blessed by the insights and resources (including Key Insights Chart and Quotes Sheet Bill offers below.

Thank you so much for letting me be with you today. I’m so grateful to be here because as millions of people do, I love National Geographic. It is one of my favorite magazines ever. The beauty and scope of it, your earnest pursuit of knowledge and truth, and then the ways you communicate what you’ve learned to be true. You pursue your work with and as art about things that matter. What is a better combination than that? So, thank you for your work.

Before I begin, I think there are a few things that may be helpful and perhaps even important for you to know about me. At this point, I’ve lost count of how many countries I’ve traveled to, where I’ve spent a decent amount of time in. I guess it’s somewhere over 80, and several of those quite a few times, actually. So I feel like I know the world a little bit– its beauties, its brokenness, its complexities, a portion of its magnitude. Even if it’s a small portion, at least I feel like I know a little of it from having been in a lot of different places.

Another thing to know is that most of my adult life, I’ve tried to engage the needs of the world by living and working in inner-city environments or in majority world environments. In other words, having seen some of the reality that is the world, one way or the other, I’ve tried to address these realities.

Another thing to know that feels important is that now, while I’ve spent so much time in the developing world or the inner city, now I do that in a different way. My wife, four kids, and I live on a small farm in the Shenandoah Valley. And one of the things we do there is offer a place of rest and spiritual retreat for those who are on the front lines of the brokenness of the world. So, at this point in my life, I’ve lived in the suburbs, I’ve lived in the inner city, I’ve lived around the world, now I live in the country— I don’t know what’s next. I noticed last year there was a lottery to go to Mars. I could sign up for that, I suppose, but you know… The ending of that story doesn’t sound very fun.

And this is important for you to know too which I’ll talk more about later. I grew up in a Christian home, I went to a Christian college, I went to a Christian seminary. For as long as I can remember, I’ve been generally pretty serious about my faith, and that was formed in a deeply Christian context.

So the story I want to tell begins in 1994. That year, I had the opportunity to go to the National Prayer Breakfast, something held here in Washington every February. It’s an event where the President shows up, and the purpose of it ostensibly is to pray for him, but he’s also attended by his wife, the Vice President, all sorts of members of Congress, all sorts of Heads of State. And then about 4,000 other people come for a continental breakfast. They gather, they pray, and they usually have a speaker of note.

In 1994, the first year that I went, the speaker was Mother Teresa. I could tell a long story about that morning, but let me just tell you, with the President of the United States on her left and the Vice President of the United States on her right, with Congress folks from everywhere, with parliamentarians from around the world, with prime ministers and presidents and leaders from around the world– by far, she was the most powerful person in the room. It was unbelievable to witness. She was tiny, barely five feet tall, so you couldn’t even really see her, and yet she was a powerful presence.

She said a couple of things that I had never heard before. Not least of which was her response to this question, “Mother Teresa, how is it that you have loved the poorest of the poor for so long?” And she said, “I don’t even understand the question. I’m just loving my husband.” Now remember, I had grown up in a Christian home, Christian college, Christian seminary, deeply formed in a Christian context–but I had never in my life heard anyone talk about Jesus that way. She was so powerful, her words were so compelling, her angle was so different. Sitting there in that ballroom at the Washington Hilton, I said, “If I ever get the chance, I’m gonna go to Calcutta and see what she’s talking about.”

Well, the chance came just a few months later. I was graduating from seminary, and I was awarded a postgraduate fellowship. It was called the Parish Pulpit Fellowship, and it was like a Rhodes Scholarship for preachers. Essentially, an anonymous donor gave a chunk of money to three of the top seminaries in the country saying, “Choose the person who shows some sort of promise in preaching, give them this money, let them do with it what they want to do, as long as it’ll help them be a better preacher, and as long as they get out of the United States for at least nine months. Beyond that, no other stipulations.”

So, all of a sudden, I had an opportunity to take a chunk of money, make it last as long as I could, and go anywhere in the world I wanted to. I put a pin in the map on Calcutta and said, “I’m gonna try to make it to Calcutta and make it back. All the other stuff that happens is important, but it feels kinda like gravy relative to finally getting a chance to go see what this woman was talking about.”

The purpose of this fellowship actually was to make you a better preacher. And I also took it as an opportunity to go around the world for 16 months, by myself, studying and experiencing inner-city ministry and models of Christian community in all sorts of global contexts. I worked with heroin addicts in Amsterdam, and homeless folks in London and various parts of Europe, Israel, Palestine, India, Nepal, Thailand, Korea, and other places, for 18 months. For me, it was a chance to get to know the world, and more specifically, the world outside the West.

Another, very personal purpose behind my trip was to try and answer a question that had been gnawing in the back of my brain for a very long time. Through a series of crises of faith and hard thinking already, I’d already come to the conclusion that the Bible is a very trustworthy document. That’s a very important question. Is the Bible trustworthy? And another really important question: Is there anything particularly unique about Jesus that sets him apart from other people?

Earlier in life, I had already done the hard work of answering those questions. And frankly, the reason for that was because I didn’t want to give my life to Christianity, and then come to find out in my 40s that it was all fake, having missed my libido in my 20’s. In other words, “If I’m living a particular way that makes real demands on me, I wanna find out if it’s crap now, not later.” There was more to it than that, but I had a real drive to ask and answer the hard questions, and I had done that. However, there was still one major question that I really wanted to answer but didn’t know how.

I am a huge believer in asking questions, and I’m a huge believer in asking the biggest questions. Of the most amazing individuals of the 20th century, of course, was Mahatma Gandhi. A remarkable man in so many ways. And this is what he said, and I quote it because it resonates so deeply with me. He said:

“For me, truth is the sovereign principle, which includes numerous other principles. This truth is not only truthfulness in word, but truthfulness in thought also. The truth that I seek is the absolute truth. The eternal principle, that is God, I worship God as truth only. I have not yet found Him, but I’m seeking after Him, and I am prepared to sacrifice the things dearest to me in pursuit of this quest. Even if the sacrifice demanded be my very life, I hope I may be prepared to give it.”

That’s pretty powerful. In other words, Gandhi is saying, “Whatever is true, I want that. And I’ll pay for it, whatever it costs.” I resonate with that. That’s the way that I feel too. That leads to another quote, from Annie Dillard’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. She goes off into the woods for a year and just writes about the wonders of nature she sees and all that she sees through it. She’s 26 years old or so. This is what she writes, and this also resonates with me in this pursuit of the question, the pursuit of the truth. She says:

“Sometimes I ride a bucking faith, while one hand grips and the other hand flails through the air. And like any daredevil, I gouge with my heels for blood for a wilder ride for more.”

What she’s saying is, “I am riding the bucking bronco of faith, and I’m gonna ride it wherever it takes me.” There is an adventure in that, and there’s a choosing in that as well.

You remember how I said I grew up Christian? Well, there were many upsides to that, but there were some downsides as well. And here it was more of the big ones. There was this question in the back of my brain, not always conscious, but when it came, always sharp, and it was prompted by this awareness: “If I grew up in Iran, I’d probably be a Muslim, likely a pretty serious one too. In fact, I’d probably be an Imam. If I grew up in India, there’s a very good chance I’d be Hindu, maybe even a Sadhu, maybe even a holy man.” So here’s the question:

Is there anything distinctively true about Jesus and about Christianity that actually sets it apart?

In other words, how do I know that my faith isn’t merely the product of my background?

Whatever we grew up with, we’ve got to answer that question, I think. Is there just one mountain with various paths, all of which lead to the summit, which is God? Is there just one box and the great religions of the world are just different sides of it? Is that what it is? Or is Jesus uniquely true?

I took this post-graduate fellowship as an opportunity to study and experience as much as I could of the five major world religions– on their terms, on their turf, with their texts, without judgment, for no other purpose than my own personal desire to pursue the truth and try to understand what might be real. I wanted to understand what they are actually saying.

Any lecture that I had ever heard about Hinduism had come from a Christian, but what kind of perspective on Hinduism are you gonna get from a Christian? You’re gonna get a really long laundry list of why it’s wrong. That’s no education. That’s not a helpful way to understand something. Same about all the others. So what are they saying actually? What are their answers to the biggest questions? And which of these world faiths seems to be most compelling in the world that actually is.

In other words, which one is gonna give the most robust answers to the way that the world actually is? So, I decided to stack them side by side, study them, and see what I learned. And more personally, I wanted to see their impact on a society that adheres to them. What’s Israel like? What’s India like? What’s Thailand like? What’s the U.S. like? What is the societal impact of a faith? Does it lead to people’s flourishing?

Now, there are some huge basic assumptions underneath this quest. Let me be clear about what my basic operating assumptions were as I did this.

First, I assume there is a way of living that will lead to the best life available to human beings. In other words, there is a Truth capital T that exists, transcending time, country, and individuals. Whatever that Truth is, it’s bigger than any country, it’s bigger than any individual, it’s bigger than any epoch, and the closer you can live to that Truth, whatever it is, the better your human existence is gonna be. Kinda makes sense, right? If there’s a Truth, if you can live closely aligned with that Truth, you as a human being will probably have a better life. It’s the way things are made. And a follow on from this assumption—whatever this Truth entails may have a pretty significant impact on what happens when your human life is over.

Second huge assumption– if this Truth exists, then somehow it must be able to be ascertained. In other words, somehow we must be able to figure out at least parts of what it is.

Third basic assumption– there is something to religion. Some sort of divine thing must exist. Perhaps the most important common denominator in human history, almost like a golden thread that ties all of human culture together, is the presence of some sort of God. You will not find an atheist culture. It doesn’t exist, at least not yet. In every culture, religion will be present in some way. There’s not one civilization or people or tribe that has not or does not have some sort of God, some sort of higher power or ultimate being, either at the beginning of their development as a society or as a clear presence within its culture from rise to fall. This is true from the beginning of human history, and I think this may be one of the strongest arguments for the existence of God. Apparently, humans just crave God.

A fourth basic assumption– if that divine thing exists, there are likely ways to know it. We could expect some form of communication between divinity and humanity. If that divine thing has communicated, it would likely be revealed in the oldest major global religions. In other words, I wouldn’t guess that a divine being would only communicate to a very, very small group of people. Again, these are all assumptions. I’m not talking about them as facts, I’m just laying out my operating assumptions.

Not too long ago, The Washington Post ran this great graphic, “What if the world were 100 people?” It’s fascinating. It breaks the world into 100 people and asks: What would their gender be? What continent do they live on? What language would they speak? What’s their housing like? What’s their nutrition like? Do they have internet? It’s very interesting. Well, what religion would they be?

It turns out that 76% of the world is one of those five religions that I’ve given on your piece of paper—either Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, and then a very, very small but very, very potent presence of Judaism. It’s very small (25 million people), but I include it because of its historicity, I include it because of its impact, I include it because of its massive influence on both Christianity and Islam. So, if this divine thing communicates, my assumption would be that it’s probably gonna speak through one of these five major religions.

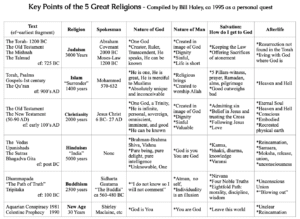

I made a simple chart at the beginning of my trip with information that mattered to me. I was simply trying to be intellectually honest and spiritually earnest in that pursuit of Truth that Gandhi was talking about. This wasn’t anything academic, it was very personal. But this is what I put together after 1995, after I returned from this trip. I asked these questions:

What are the texts of these five great religions?

How old do they go back?

Not only that, but when do we have the earliest fragments of the texts?

In other words, how much slip can there be between the founder of the religion and the written interpretation of whatever that founder said?

Who is the spokesman? Would I wanna follow that person?

That’s a really important question. Is he a good guy? How did he behave?

How does this religion understand the nature of God? The nature of humankind?

What does this religion tell me I have to do in order to be saved?

Whatever “saved” means, what does it require of me?

What’s its vision of the afterlife? Is it compelling? Does it make sense?

Then, it was just a matter of going to these different countries and trying to read as much of the primary texts as I could– not simply to answer these questions but just to see what they were saying. When I got back, I put it all together.

Other important questions I have thought of since would be–

What’s the view of suffering and evil?

What does one do with one’s own suffering? How does it understand that?

And then there’s the societal vision.

The societal vision of a religion is very, very important when you’re in that country, seeing the way it is actually working out. I’ll talk about that more below when I talk about India.

What are a human’s obligations to others? And why? And which one’s? A huge question.

There is so much more that I could have included, but this was the form my mid-90’s personal pursuit took as I tried to get a handle on really important ideas that would hopefully lead me to the life that is really life, to Truth. I will just point out a couple of things on the chart that mattered to me.

First– What are the earliest fragments that we have that portend to be from the religious text? Hinduism is really hard. It’s a 5000-year-old religion, but the earliest thing ever written down is right around the time of Christ, 2000 years ago. There are reasons for that, but it doesn’t change the fact that we really don’t have a lot from when that stuff was actually being written down into Script.

Islam is the youngest of all these religions, but it’s very hard to find fragments older than about 300 years after Muhammad was alive. That’s interesting. And who was the committee that wrote down what he said and determined what he had said and what he hadn’t said?

Christianity, early 100s, not too bad, actually. In antiquity, that’s a blip. I can be confident-ish that the translation I’m reading in English is based on a pretty rigorous and academically approached reflection of what we actually have in fragments in papyrus. All that was of note to me.

Next– What can we learn from the lives of the great religious founders? Let me first of all say, I love Siddhartha Gautama. I think that guy was amazing. As you know, Siddhartha Gautama was the founder of Buddhism. He became the Buddha. He was a Hindu. He realized the shortcomings of Hinduism, rejected it, sat under the bodhi tree until he could figure it all out, and came up with the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. And the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path are not bad. That’s impressive!

Here you have a guy sitting under a tree separated by the Himalayas from Israel, when Jeremiah and Isaiah are prophesying. He rejects the known to pursue the Truth and comes up with something that’s not so bad. That’s impressive to me. I would follow the Buddha. He’s a good man, in my opinion. But he and Buddhism believe that the material world doesn’t exist; it’s an illusion. Senses are bad in any direction. Any sort of sensual physical experience is bad, because it’s all an illusion. The only way to achieve salvation is to escape the illusion of what you think is real and realize that nothing is real; even your self, your individuality, is not true. You are anattā, not-self.

I’m not so sure about that, especially considering how complicated it gets when you want to know what to do with the suffering you experience. I remember reading a book by the Dalai Lama; he was writing about the death of his mother, and he said, “I grieved her.” He said, “I knew that as a good Buddhist, I shouldn’t feel badly for her passing. But I did.” That kind of gets at it.

Studying the life of Muhammad and how it was that Islam spread was eye-opening. I realized, I don’t think I would want to follow that man. “Convert or die” goes back to the very foundations of Islam. Muhammad himself did it. That was interesting to me.

It was interesting to research and read through the different depictions of the afterlife and wonder which I would hope for. And then, salvation. How do I get to God? The law of karma operates very significantly. You get what you pay for. Whatever you do comes back at you. Or, you must do X, Y, and Z in order to present yourself worthy. For me, for my personality, those felt heavy.

Intellectually, historically, archaeologically, and spiritually, Christianity came out on top for me. But let me say two things after having gone through this exercise.

First, there are great things to be learned from each of the religions. Each of the world religions has a lot to offer. It’s been said that since God is Truth, all truth is God’s truth. So, if there’s anything that’s true or valuable in another religion, we can thank God for it and we can learn from it. In fact, there are some things that other religions actually do better than Christianity or help us understand better than Christianity, and we can learn from them.

C.S. Lewis said in Mere Christianity, “If you’re a Christian, you don’t have to believe that all the other religions are simply wrong all through. If you’re a Christian, you are free to think that all these religions, even the queer-est ones, contain at least some hint of truth.”

If we adopt an attitude that views different religions as genuine quests for truth as opposed to threats, we can come to a healthy respect for those who sincerely believe in the historical and global religions, whatever they are. Simply because a person believes differently than we do does not mean that they aren’t spiritual or thoughtful and that we can’t learn from them as we also seek to share the truth that we’ve come to know.

Second, these religions can’t all be totally true. Different religions, at least their founders, make mutually exclusive claims. It may sound good to say that all ways lead to God, or that all colors bleed into one, or that each of these religions is just one side of the same box, but the religions and the founders themselves don’t allow this view.

I’ve often wondered what a conversation between Jesus and Muhammad would be like on this count. “Well, Jesus, you’re an awfully good man, but surely you aren’t God. Only Allah is God. And as a matter of fact, I’ll have to kill you for saying that you are God and he isn’t.” That’s how a conversation between Muhammad and Jesus might go.

Or Buddha and Muhammad. What would they talk about? “Muhammad, there is no God and you are not his profit.” That’s what Buddha would say. What was Buddha’s response to the Hindus? He rejected it, he said that is not true.

Or the Hindus to the Jews. “Your prayer, ‘Hear O Israel, the Lord. The God is one,’ is nice, but you should really change it. You should change Israel to India, you should change the Lord to Brahma, and you should change the number 1 to 33 million.”

Or Jesus, to all of them. He says, “I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to God except through me.”

It’s very interesting that when you look at them on their face, the world religions don’t excuse us from the work of reckoning with their major disagreements. They don’t allow us the comfortable stance that they’re all simply different ways to God. I do not find that position to be intellectually honest. But I would say this, it wasn’t the intellectual stuff, it wasn’t all this research that actually tipped me over into a deeper faith.

If you’ve been to India, you know it is quite an experience. I love India, and I hate India. I’ve talked about it like an infection that gets in your blood; once you go there, you can’t get it out of your system. It’s a remarkable country.

I was traveling overground from Bombay to Calcutta, again up into the Himalayas and through Rishikesh, and then through Varanasi, which is the holy city for the Hindus. If you die in Varanasi, your reincarnation cycle immediately stops. So it’s actually a city of death. People come to die in Varanasi; there are cremation ghats everywhere. There are people waiting to die in hotels; there are people waiting to die in the streets. And there are always dozens and dozens of fires burning along the Ganges. Whenever the water level recedes, it uncovers all of the half-buried remains of these folks that I’m talking about. It is a dark place.

From there, I continued on to Calcutta, where I got to be with Mother Teresa for a few weeks. Talk about contrasting responses to the core questions– What is the purpose of life? What do you do with the most vulnerable?

Who was this person and how did she do amazing work? Her witness, her devotion to Jesus, and the love of the least were the last little bit of convincing I needed to say, “Yeah, there is something really different about what Christianity offers the world than what I just experienced.” Getting to meet her, even having a few short conversations with her changed my life.

Malcolm Muggeridge was a journalist in Britain, and he was who put Mother Teresa on the map. He met her in the mid-70s. He was an atheist at the time, but even before he converted, which he did, he wrote this about her:

“Something of God’s universal love has rubbed off on Mother Teresa, giving her homely features a noticeable luminosity. It was impossible to be with her, to listen to her, to observe what she was doing and how she was doing it, without being in some degree converted.”

And Muggeridge was. A noticeable luminosity. In other words, there was a presence within her that radiated out of her, and when you were with her, you felt like you were in the presence of the other. I can attest that was really true, both when I was one-in-4000 and then when I was one-on-one. Just being with her, even in a huge ballroom, had an effect. It was her life and witness that really tipped me over to say, “I’ve seen what I need to see.”

So then, I journeyed overground from Calcutta to Kathmandu, which is not an easy trip by one’s self, and then alone into the Himalayas to get to as high as I could on that particular trip—17,000 feet. I was able to see Everest off in the distance. I wanted to get as high as I could on my globe and basically say, “God, having seen so much, having asked these questions, I believe, have my life.”

But do you know what it was that really tipped me over? It was my deep realization that I am not good enough, that I am not disciplined enough to make my way to God on God’s own standards or my own strength. If life is about karma, I am screwed. If it’s about devotion to religious discipline and really lining up with a narrowly religious way of life, again, I’m screwed. I know me too well. I can’t even live up to my own standards.

If there’s any hope for me, it’s because there’s something called grace, which is when we don’t get whacked when we deserve to get whacked. I’ve given you a lovely quote from Bono—he says it well, obviously better than I could. But as he says, “I’d be in big trouble, if karma was gonna finally be my judge, I’d be in deep shit.” And it is true. And he goes on to say, “Christianity is the only thing that offers grace,” and it’s really true of all these world religions.

Here’s the kicker. Remember I got that great post-graduate fellowship award? Well, I realized really early in this trip that actually, this wasn’t so much about any sort of recognition or award or anything. God was giving me the opportunity to take a trip around the world with him in a way where I could leave all of my stuff at the door. There were no expectations on me, nobody knew my resume, nobody knew who I knew. I had really no responsibility, I had no importance. I was thrown into cross-cultural experiences where I was not in power, often not even able to use the primary gift of language to communicate.

God was basically saying, “Bill, you know me the way you think you should know me. I want you to know me the way I want you to know me. It’s gonna take removing you from all that stuff and going around the world with you for 18 months, so that you can know me the way that I want you to know me and what I want you to know about me.” At the end of that trip, I felt the Lord saying, “Now you know that I love you, I’m with you, and you can trust me.” And those three things have undergirded me ever since.

I don’t offer these thoughts today in a way to say, “This is what you should believe also,” but I guess my encouragement would be for all of us to do the hard work of being intellectually honest about the very biggest questions. And then, let us come to our conclusions, so that we can live full-out in whatever direction is revealed to us as the way things actually are. Doing this, we can live in line with capital-T Truth and have the best possible human existence relative to that Truth and hopefully do some good in the world.