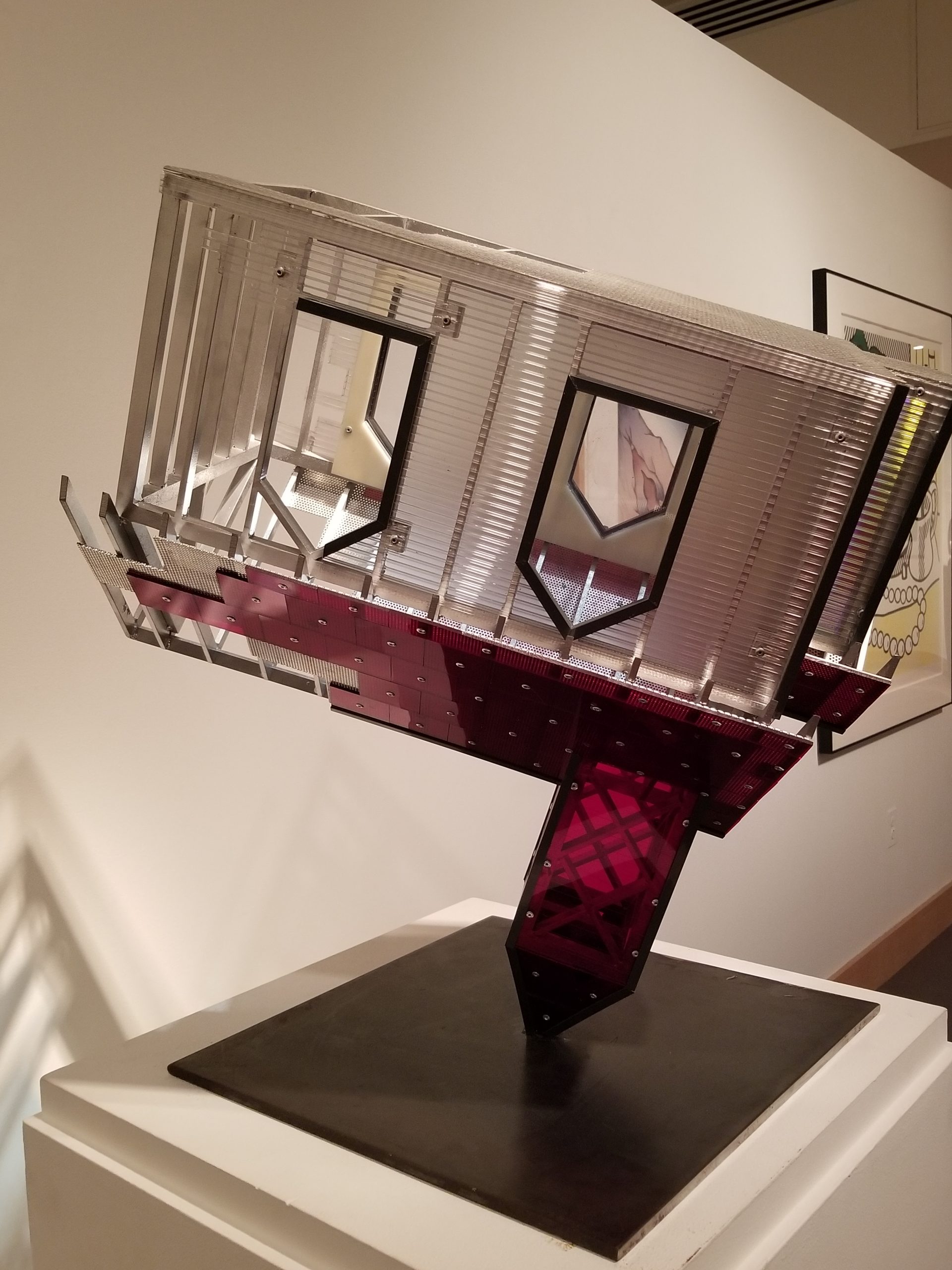

Nearly two years ago my husband and I visited the Boca Raton Museum of Art on our travels through Florida. There I encountered a deeply moving, profound, disturbing, and yet in some ways prophetic piece of art. A model of a life-size work, this piece by artist Dennis Oppenheim from 1997 is entitled “Device to Root Out Evil.” The model, like the actual life-size piece, displays an upside-down New England-style church pointing towards hell rather than heaven. Over the last two years, I have contemplated this work of art numerous times.

(Photos by the author 2019 taken May 2019 the Boca Raton Museum of Art)

My first encounter with Oppenheim’s work helped me identify grief, sorrow, and lament I have experienced within the western Christian Church. And by “Church,” I mean the various forms of Church in the west, not just one particular church or even denomination. Christian churches across the denominational spectrum have all had abuses, scandals, disappointments, and failures come to light in recent years. We have witnessed failures in fidelity to scripture, in justice, finances, ethics, sexual behavior, racism, sexism, and elitism as well as broader failures of not being community or serving well the communities where they exist.

Recent events have prompted yet another reflection on Oppenheim’s work. Post-mortem revelations about two Christian men whose ministry I admired and learned from are difficult for me to process and have brought me to a place of deep lament. They are Jean Vanier and Ravi Zacharias. Vanier seemed to have the right stuff, to care for the poor and the vulnerable, in particular the disabled. And yet, as a spiritual director, he abused his position of authority and trust (Bill Haley reflected on this Here). While Ravi Zacharias sparked a world-wide apologetics movement and brought the transformative message of the Gospel to thousands throughout his decades-long ministry, we as Christians must also confront, squarely, what a recent independent report documents in harrowing detail: that he also used his positions of organizational and spiritual power to prey on women. The report “conclude[s] that Mr. Zacharias engaged in sexual misconduct.”

Thus, my mind turned once again to Oppenheim’s work. To me, this image of an upside-down church represents a shaking-up of the Church in the west, a cleansing. It is as if someone picked up the church and emptied out all that was inside. As I contemplate this image, it moves me to prayer and self-examination. Like every other person, I have sinned in some way and fallen short of God’s expectation of me as a leader and as a disciple of Jesus. (Romans 3:23)

The shake-up continues. We are each accountable to God for our own sins, but as these examples show, no sin is truly private. Sins affect others in the Body of Christ, the Christian community as a whole, and others who are not Christians. Shaking-out the church in a context of a ministry failure may mean that innocent people lose work or that some people question their own faith, to say nothing of lost possibilities for evangelism among those outside the church. Abuse can present itself to the abused in different forms throughout their lives, affecting others who were not parties to the abuse. This makes our response to private sins becoming public (Luke 12:3) all the more urgent, and equally demands both humility in our response and a care for all those who have been affected by the tragedy of sin.

Unwelcome events, therefore, present an invitation to new ways of living out our Christian faith both individually and communally. What invitation might we take from this work of art and what it represents? As we enter the Lenten season and make time in our lives for some serious reflection with God, I see three invitations.

First, it is an opportunity to seek God with our whole heart, soul, mind, and strength (Luke 10:27). Spiritual practices like self-examination, confession, repentance, lament, and reconciliation are ours for the taking. It is a time for honest questions in our prayer life. We might ask God where we have failed to show up and engage others.

Second, it is the opportunity to love our neighbor as ourselves (Mark 12:31)– both in ways that put our love and care on display and in ways that limit the possibilities for grievous errors in our church life and ministry to take place in the future. How might we serve others in practical, tangible ways, albeit at a social distance?

Third, after praying, it is an opportunity to rethink mission in our local contexts. What is one action we might take to serve the common good? This might be in our local churches, or perhaps it is in our neighborhoods or towns.

The invitation to wrestle with God is a daily option. How is the state of our own soul, in what ways do we demonstrate practical, tangible love to others, and how might we move to more intentional practices of spiritual formation that nurture our own growth and the spread of the gospel, honorably and with accountability?

Oppenheim, as far as I know, was not a man of the Christian faith. Whether or not you connect with this piece of art or find it scandalous or even blasphemous, how might a meditation on this upside-down church in these present times represent an invitation to repentance to all of us who profess the Christian faith?

There is no perfect, pure Church; that notion simply does not exist; varying degrees of health, yes. The Church is comprised of people– all of us hypocrites at some level– not mere buildings. Biblically, the Church is a people who follow wholeheartedly after Jesus and are known for their love. Are we known for our love? (John 13:35) It is a good question to ponder this Lent.

Rev. Mary Amendolia Gardner is a DMin. candidate at Wesley Theological Seminary and a Spiritual Director with Coracle.