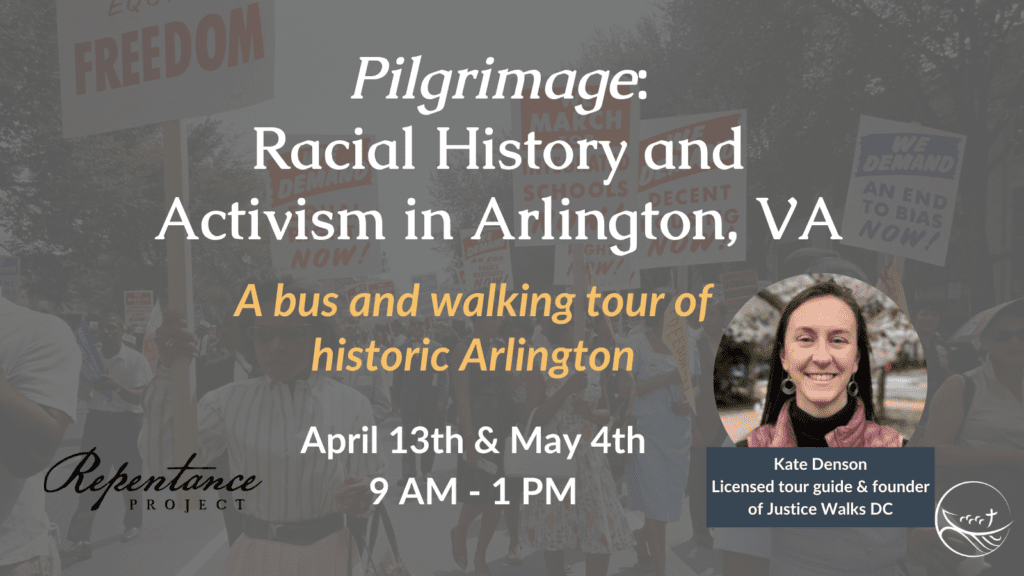

On March 28th, I had the opportunity to chat with Kate Denson of Justice Walks DC. Kate, who is on staff with InterVarsity as their National Director of Justice Programs, is also a licensed tour guide who has been creating and leading tours in and around Washington, DC for over a decade. It began as a passion project which she used as a way to introduce the people she met in her life as a campus minister at Georgetown University to the warm and welcoming DC culture she had come to love from living in Anacostia. Today, Justice Walks DC has grown into a small and robust offering for those who wish to not only learn the history of DC and the surrounding areas, but also wish to know the story of the places and people who have shaped and continue to shape the area.

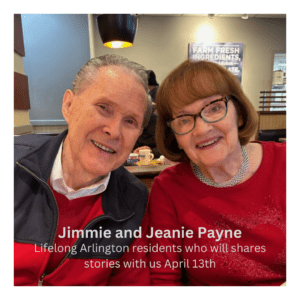

[Kate will be leading our “PILGRIMAGE: The Racial History and Activism in Arlington, VA” offering April 13th (full) and May 4th. ]

Kristy: Hi Kate. First of all, thank you for taking the time to chat with me; let’s get started. How did you come to the Washington, DC area; otherwise known as the DMV?

Kate: That’s a good question. Well, I grew up in Texas, and when I was a senior in high school applying for college, it came down to deciding between the University of Texas, Baylor, and William and Mary. I initially thought William and Mary was out of reach for myself but then I got in and even got a scholarship; apparently, I was doing better academically than I thought. The day I was supposed to make my final decision, the war in Iraq broke out. My dad drove me down to take a look at both Baylor and UT that same day. At Baylor, they were having a vigil. At UT Austin, they were having a walk-out. I definitely resonated more with the walk-out than the vigil, but that evening I went to a Bible study about “Just War Theory” where I met a guy who was on Spring Break from William and Mary. He said to me, “If you want to stay in Texas, this direction makes a lot of sense and it’ll be great, but if you want to go to DC, you need to go to William and Mary.” I hadn’t necessarily thought, “Oh, I want to go to DC,” I never even looked at schools in DC but found that many students at William and Mary are from the DC area and wind up in DC after graduation. That wound up being true for me too. After graduating, I came on staff with InterVarsity right away, moved to Anacostia in South East DC, and that’s history. That was almost 17 years ago.

Kristy: Seventeen years is almost long enough to say that you’re from DC; would you say that you’re from DC?

Kate: I would say that I’m from DC more than I’m from anywhere else. Here’s the thing though, I’m married to a DC native who would not let me say that, so I’ll say I’ve lived in DC longer than I’ve lived anywhere else. I’ll never pretend to be a DC native, but it is the most solid home I know.

Kristy: In your story, it sounds like there was something stirring in you regarding justice. You noticed the different ways the schools were responding to the break out of war in Iraq. Is that your earliest or strongest memory of God stirring your heart for justice?

Kate: I don’t know that it was necessarily that experience as a starting point for me, the starting point was earlier. In high school, I remember taking some type of quiz in Government class where I noticed that I scored very differently from most of the people I went to church with, which made me think, “Oh, this is interesting.” For my dad who has always been left leaning, it surprised and concerned him to learn how starkly conservative the influences around me were. He then started just leaving Jim Wallis articles around the house or suggesting, “I feel like you should read this,” or “Take a look at this.” My parents knew my faith was really important to me and wanted to make sure I had balanced exposure. Also, our church had mission trips every summer and that was always my favorite activity every summer. There is something about practicing my faith as service that has always been a really important part of faith for me, so missions trips were certainly part of that. As far as justice goes, I don’t think you can go to a low income place which is where many of these mission trips went to, like a rural community or a Native reservation, and not ask the questions of, “how is this the life that the people I’m meeting have, and I have a very different life where I don’t need teenagers to paint my house?” Whether the questions were addressed or not or whether I even asked the questions verbally, there was some sense that people here are living very differently from how I’m living and something not being right about that.

Kristy: Were there people in your life who you could ask these questions or process these ideas?

Kate: The church I grew up in was borderline mega-church, and I wasn’t a very loud kid, so it was just harder for me to ask. I think I’m a pretty outspoken leader-type person now but that didn’t develop for me until during or after college. Tour guiding has done a lot in helping me grow in my confidence with public speaking which has been a great side effect for me in life and other ministry. Anyway, there was this one youth pastor who pursued a relationship with me towards the end of high school; she started a group for senior girls. I spent a lot of time in that group taking in Christian ideas, and nobody was asking me what I thought or equipping me to communicate anything to anyone else. In his book Irresistible Revolution, I believe Shane Claiborne uses the term “Spiritual Bulimia” meaning that you’re taking in a lot, but you don’t really have a way to live it. That feels like a lot of how I grew up; young people are not expected to have something to contribute, so they’re being told a lot and asked to listen a lot but not given a lot of opportunities to do anything with it. I’d actually like to go back and reread that book now 20 years later since so much of what was said in it resonated with me and was pivotal in my development. When I went to college, I got involved with InterVarsity. Although I grew up Methodist, I really liked that the people I met in InterVarsity had a faith that seemed to affect their life; practicing their faith wasn’t a thing they did a few times a week, it was actually foundational for how they thought about their lives and I wanted that for myself too.

Kristy: At some point after moving to DC, you realized that you enjoyed learning about the rich history of the city and sharing that with others. There are many tours offered around the city, but few will weave in stories of justice in what they’re sharing. How did you determine that telling stories of justice was important in the tours you offer?

Kate: Yes, faith AND justice weaved together. What I have found is that there are a lot of intersections around faith and justice, and the built environment. When I first moved to Anacostia, I started going to St. Teresa of Avila where Father East was the pastor. Aside from the church I grew up in as a child, I would say that St. Theresa of Avila is really the church that raised me as a minister, taught me how to think about scripture and how to think about the community. One day, I tagged along on a tour of Anacostia he was giving to Sojourners interns. That was an early influence of how helpful it was to see this community through the lens of a pastor who clearly cares about justice and faith together; he was walking us around while showing us the history of the community and explaining things that wouldn’t regularly be on a tour like walking us into a corner store to show us the plexiglass. He was expanding our ideas of what places and things were worthy to be talked about. Another influence was an InterVarsity trip I took to Camden, NJ in college; this is where I was introduced to Shane Claiborne. We went on what they called a “reality tour” which allowed me as a sociology major to see how sociology meets faith meets built environment, that was really cool. Georgetown University also has something called the Center for Social Justice (I was a campus minister there my first five years in DC) and they would do bus tours around the whole city. I would take notes and try to remember everything they said so that I could go back and mimic the tours myself.

I eventually took a course on how to be a tour guide which wound up being a real game changer for me. Now, everything else I learn from lectures or reading a book or reading an article or even having people on a tour who know more about the city than I do, the learning keeps building on itself. When you’re living in the same city for a long time and you’re curious about the city, pieces will keep fitting together. Keep in mind that in those first five years, I worked in Georgetown but lived in Anacostia; two starkly different places and even more so 20 years ago. I wasn’t sure how often my folks in Anacostia went to Georgetown, but I definitely knew that my folks in Georgetown rarely if ever went East of the river. I wanted the people I met in Georgetown to see the city how I saw the city. Their world was West of the river, but if your world is East of the river the experience is different. I thought about this contrast a lot and felt very thankful that Anacostia was where I got my start and the place that formed me as a young person in DC.

Kristy: When you take a person or a group on a tour, what do you hope they leave with?

Kate: That’s a great question, and I would say that every tour has a different underlying goal. I developed my first tour just after I got married and moved West of the river; it was a tour of H Street. Living West of the river, I noticed that people didn’t have a certain intuition I developed while living in Anacostia; something as simple as saying hello on the street. Seeing the dramatic racial tension and divides on H Street that, which maybe existed in Anacostia but were not the pronounced cultural clashing like you would see on H Street in 2013, made me think that although a few tweeks would not fix gentrification they could at least help you be more respectful and maybe go out of your way to get to know someone who has lived here longer than you. I felt like I was watching two worlds where these new wealthier people were living in one world and people who had lived there forever were living in this other world, and they weren’t interacting. I thought, “something isn’t right here” and, in my belief system, I felt very strongly that the one coming in from the outside who has the socio-economic power has to be the one to make the first step. That’s just the way of Jesus; it is the responsibility of the one who is new. Someone might say that it should be the other way around, but when the power dynamics are what they are, the situation is different. I wanted to create a tour that would encourage people who were gentrifiers, honestly, to get to know their neighbors and neighborhood and think about what was here before you got here. I didn’t have the posture of, “you shouldn’t be here” or “I’m mad at you that you came”; I just felt like there were things I had learned that might help smooth tensions a little.

Kate: That’s a great question, and I would say that every tour has a different underlying goal. I developed my first tour just after I got married and moved West of the river; it was a tour of H Street. Living West of the river, I noticed that people didn’t have a certain intuition I developed while living in Anacostia; something as simple as saying hello on the street. Seeing the dramatic racial tension and divides on H Street that, which maybe existed in Anacostia but were not the pronounced cultural clashing like you would see on H Street in 2013, made me think that although a few tweeks would not fix gentrification they could at least help you be more respectful and maybe go out of your way to get to know someone who has lived here longer than you. I felt like I was watching two worlds where these new wealthier people were living in one world and people who had lived there forever were living in this other world, and they weren’t interacting. I thought, “something isn’t right here” and, in my belief system, I felt very strongly that the one coming in from the outside who has the socio-economic power has to be the one to make the first step. That’s just the way of Jesus; it is the responsibility of the one who is new. Someone might say that it should be the other way around, but when the power dynamics are what they are, the situation is different. I wanted to create a tour that would encourage people who were gentrifiers, honestly, to get to know their neighbors and neighborhood and think about what was here before you got here. I didn’t have the posture of, “you shouldn’t be here” or “I’m mad at you that you came”; I just felt like there were things I had learned that might help smooth tensions a little.

Since the H Street tour, I’ve developed tours in Anacostia, U Street, Capitol Hill and Georgetown. It has always been important to me to have aspects of the tours that are more current which is something that’s different from a lot of other tours; for example we would stop at Busboys and Poets not to just say, “this is a cool restaurant” but to really examine that Busboys does a lot of good and, sadly, I think in most instances gentrification accompanies it.

I also think about the people who come on the tour and how I can help them think about their engagement. Other than understanding the history, what I’m saying to them is, “Hey, if Busboys and Poets is the extent of your engagement with Black DC…nah, nah, nah we didn’t get it, we didn’t get it; that’s consumerism not meeting humanity.” There are people who believe that if they’re going to the cool places they’re engaging the community. I think there are better ways to be a neighbor that are not performative. The Capitol Hill tour I wrote is a little different in that you don’t tend to engage with a lot of people whereas the others, like H Street, it is pretty common that there will be engagement with a person on the tour which is something else that I’ve done as a tour guide which is a bit abnormal and super risky. I’m basically giving the floor to a stranger and seeing what happens and that can go a lot of ways, but I like doing that; most times, it goes pretty well. One time I saw this guy coming out of the Downtown Locker Room wearing a “Empower DC” or “One DC” tee shirt, and I thought this could go really bad because he could be like, “No, I don’t want to talk to you.” Later, I realized who he was when I saw him at another event, he was community organizer, Maurice Cook, of Serve Your City and he wound up being gracious with his time and gave our group wonderful insight into the community there. Sometimes I’ve even set it up where there’s a pastor on H Street who will come talk to a group, but it’s not always possible to find someone who can come talk to a group.

I also think about the people who come on the tour and how I can help them think about their engagement. Other than understanding the history, what I’m saying to them is, “Hey, if Busboys and Poets is the extent of your engagement with Black DC…nah, nah, nah we didn’t get it, we didn’t get it; that’s consumerism not meeting humanity.” There are people who believe that if they’re going to the cool places they’re engaging the community. I think there are better ways to be a neighbor that are not performative. The Capitol Hill tour I wrote is a little different in that you don’t tend to engage with a lot of people whereas the others, like H Street, it is pretty common that there will be engagement with a person on the tour which is something else that I’ve done as a tour guide which is a bit abnormal and super risky. I’m basically giving the floor to a stranger and seeing what happens and that can go a lot of ways, but I like doing that; most times, it goes pretty well. One time I saw this guy coming out of the Downtown Locker Room wearing a “Empower DC” or “One DC” tee shirt, and I thought this could go really bad because he could be like, “No, I don’t want to talk to you.” Later, I realized who he was when I saw him at another event, he was community organizer, Maurice Cook, of Serve Your City and he wound up being gracious with his time and gave our group wonderful insight into the community there. Sometimes I’ve even set it up where there’s a pastor on H Street who will come talk to a group, but it’s not always possible to find someone who can come talk to a group.

Kristy: You mentioned gentrification which is something that is happening in cities across the nation. How do you invite people to engage the issue of gentrification in healthy, community building ways?

Kate: There’s much broader socio-economic realities and policy realities that are things that I don’t have a lot of expertise on and I always want to be sure that I name that because I think it is important to be thoughtful about things like affordable housing. I live in a mixed income community, and it was controversial when it came in. I didn’t know that when I moved there but now I know that, and I can live repentantly in light of knowing that at one time the 134 units where I live on Capitol Hill were all home to low-income families. Now, one quarter are home to low-income families, and the other 75% of us, to some people, don’t belong here, this shouldn’t be our home, we shouldn’t live here…and yet I do. So how do I be somebody who does right by my neighbors?

When we moved here, it became evident pretty quickly that when there were community events (i.e. neighborhood board meetings or parties) there would be 80% people of color, mostly Black, attending. Our neighborhood is probably half people of color, mostly Black, and half white people. What I realized was that the white people weren’t showing up to the parties, why is that? I could speculate on why they weren’t showing up, but I could also just show up; I try to do what I can to be involved. I do know that there is a sense that, “those people don’t want to be involved; they don’t want to spend time with us.” I’m careful not to give off the air that I think I’m better than anyone else, and I think that’s basic Christianity 101; love your neighbor. I said all of that to say that when I think about gentrification, I just want to be humble and recognize that there’s blood on my hands, there’s blood on a lot of our hands, we’re all here on Native land. There’s a reality that our racialized landscape is complicated. And yet, when I walk into a situation and I know that I have a degree of social power I can choose what to do with that. Hopefully, I’m going to choose to do what I think Jesus would choose to do.

In my early years it was important to me to go to a church that had been in the community before a lot of gentrification started to happen. There’s an article that came out over ten years ago in Oakland, CA entitled “20 Ways To Not Be A Gentrifier”; I have appreciated some of the things on the list and really resonated with them like, “Smile and say hi to your neighbors every time you see them…” I love that the author understands the internal dialogue because they continue with, “…even if they seem scary or don’t say hi back.” I used to print this article out to give during tours because it addresses a lot of the things I feel were important about engaging, neighboring, and posture. Also, a few years ago, I created language of neighborhood engagement around five Rs: instead of being here to give, you’re here to receive; you’re here to offer respect (i.e. using Sir or Ma’am, saying please and thank you, being extra respectful etc.); you’re here to risk (i.e. visit a church you’ve never been to, start a conversation with a neighbor, etc.); recognize good that’s already there (instead of looking for brokenness); and rejoice in new relationships (new relationships should be a place of joy and people should not be viewed as projects). Neighboring is a relational state of being; it is the opposite of the Beloved Community to see being with others as a chore.

In my early years it was important to me to go to a church that had been in the community before a lot of gentrification started to happen. There’s an article that came out over ten years ago in Oakland, CA entitled “20 Ways To Not Be A Gentrifier”; I have appreciated some of the things on the list and really resonated with them like, “Smile and say hi to your neighbors every time you see them…” I love that the author understands the internal dialogue because they continue with, “…even if they seem scary or don’t say hi back.” I used to print this article out to give during tours because it addresses a lot of the things I feel were important about engaging, neighboring, and posture. Also, a few years ago, I created language of neighborhood engagement around five Rs: instead of being here to give, you’re here to receive; you’re here to offer respect (i.e. using Sir or Ma’am, saying please and thank you, being extra respectful etc.); you’re here to risk (i.e. visit a church you’ve never been to, start a conversation with a neighbor, etc.); recognize good that’s already there (instead of looking for brokenness); and rejoice in new relationships (new relationships should be a place of joy and people should not be viewed as projects). Neighboring is a relational state of being; it is the opposite of the Beloved Community to see being with others as a chore.

Kristy: What do you want people to know about Justice Walks DC as well as what they can expect for the upcoming “PILGRIMAGE: Racial History & Activism in Arlington, VA” tour this Saturday, April 13th?

Kate: Justice Walks DC has been a personal project and is pretty small. On average, I probably give about 20 tours a year because I have a full time job that’s not this. Around COVID, I developed a website which has done a lot to help people find me who wouldn’t have found me otherwise. I’ve often been very humbled by the kind of people I get to give tours to and share with. This past summer I got to give a tour to a group of college professors who work at the intersection of art, history, and memory. Another week I had Muslim ministers who work in social justice spaces. Then another week I had Israeli and Palestinian principals who co-create schools together. With all three of these groups, I’m thinking, “Wow, I bow in your presence” because in all of these instances I’ve felt like I am out of my league.

These have been real awesome opportunities that God has used to help me develop the broader posture of how I seek to be in the world; especially when I walk into a tour and quickly realize, “Oh, I’m among some of the greats in the world.” There’s a way to give a tour where your posture says, “I know all the things and y’all don’t know nothing,” but I like to lead a tour where it’s like, “we’re all here together encountering this place and this is a conversation where all of your thoughts are welcome and invited.” These types of groups choose my tours because they want a tour that isn’t going to be totally out of sync with their values. A couple of times I’ve been asked to write a tour for a purpose and I have done it for pay like I have for Sojourners and Repentance Project/Coracle, and I’ve also written tours as part of my work with InterVarsity and Casa Chirilagua where I also work.

These have been real awesome opportunities that God has used to help me develop the broader posture of how I seek to be in the world; especially when I walk into a tour and quickly realize, “Oh, I’m among some of the greats in the world.” There’s a way to give a tour where your posture says, “I know all the things and y’all don’t know nothing,” but I like to lead a tour where it’s like, “we’re all here together encountering this place and this is a conversation where all of your thoughts are welcome and invited.” These types of groups choose my tours because they want a tour that isn’t going to be totally out of sync with their values. A couple of times I’ve been asked to write a tour for a purpose and I have done it for pay like I have for Sojourners and Repentance Project/Coracle, and I’ve also written tours as part of my work with InterVarsity and Casa Chirilagua where I also work.

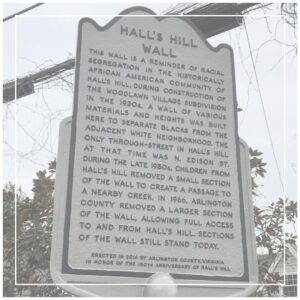

The process of writing a tour is something I really enjoy. Writing for this particular tour has felt something like writing a sermon. I started off thinking about the goal and the arc; using Wikipedia is part of my early research. Next I begin to look at the built environment to get a sense of what are the big stories and what are the sites that cover those stories. The find for this tour which really opened up the whole tour happened the day I did my first drive around and wound up at the Arlington Historical Society where I learned about an initiative that had started just a month before. The city started installing these stones outside of places where people had been enslaved. In my other tour guiding work, particularly the tour I wrote that goes past places on the National Mall where there were slave markets. The plaque that’s there, although better than nothing, is not evocative or artistic or at all sufficient for the magnitude of the subject. We can’t talk about slavery and just have a few disembodied factual words to communicate this massive evil and sin. But, in Arlington, the idea of these stones, similar to the Stolperstein in Germany, came up a lot in my research along with the work of Bryan Stephenson with the Legacy Museum and National Memorial for Peace and Justice.

I felt like it was a Holy Spirit moment for me to see that this type of work is beginning in a community close to DC and that it’s so close to Coracle’s office considering all of the historical work and advocacy Coracle has done in the Shenandoah Valley. Since this project is still so new and will need lots of encouragement to get momentum, I thought how appropriate for Coracle to now be part of the Arlington community and maybe part of that advocacy and encouragement. In addition to this fledgling project, I also had a couple other finds that have informed my development of this tour such as the old boundary stone and the Queen City memorial. I’ve really learned a lot on this journey and look forward to leading this tour with Repentance Project/Coracle folks who maybe live in Arlington and can help weave together stories that need to be lifted up.

Kristy: Kate, thank you so much for taking the time to share with us. Do you have any final thoughts you want to share with folks?

Kate: Yes, come on the Repentance Project/Coracle tour!!