There is a way that seems right to a person, but in the end its way is death.” – Proverbs 14:12

Two only sons, each deeply loved by their father, stumble up a mountain heavy with the wood of their own sacrifice upon their shoulders. One is named Isaac, and his sacrifice is defined by a willingness to inflict violence as an act of faith. The other is Jesus, and his sacrifice is defined by an act of faith refusing the use of violence (John 18:36).

Over the next three months, an intergenerational conversation involving nine different churches and organizations and over forty people, will be seeking biblical wisdom on the relationship between Christian faith and violence/nonviolence. We’d love for those not able to participate in person with this Crucial Conversation to track along with us, both through this Valley Newsletter, and the “Conversation Teasers” we will be sharing via Instagram @kenvalleycoracle

Over the next three months, an intergenerational conversation involving nine different churches and organizations and over forty people, will be seeking biblical wisdom on the relationship between Christian faith and violence/nonviolence. We’d love for those not able to participate in person with this Crucial Conversation to track along with us, both through this Valley Newsletter, and the “Conversation Teasers” we will be sharing via Instagram @kenvalleycoracle

Bill Haley wrote recently in an article that “the biggest story on our planet is the battle between Good and Evil, between God and Satan, and this plays out all throughout Scripture and down through history and is raging today.“

For the church in America where Christian nationalists (among others) are normalizing violence within their political rhetoric, the question we want to ask of Christian faith is, what is the church’s relationship to violence in our battle to overcome evil?

Can Christians use violence to overcome evil, or in using violence do we simply become evil ourselves?

The story of Genesis 22 and Abraham’s call to sacrifice Isaac on Mount Moriah, if we are honest, is among the most offensive stories in the Bible to modern sensibilities. At a glance it seems to be depicting the strange schemes of a borderline schizophrenic god: think about it, first, you are barren and childless, then after a uniquely long and painful wait I’ll miraculously give you a son, then once you have a son I’ll call you to sacrifice him, then for the grand finale at the last second I’ll stop you and say it was all just a test.

The story of Genesis 22 and Abraham’s call to sacrifice Isaac on Mount Moriah, if we are honest, is among the most offensive stories in the Bible to modern sensibilities. At a glance it seems to be depicting the strange schemes of a borderline schizophrenic god: think about it, first, you are barren and childless, then after a uniquely long and painful wait I’ll miraculously give you a son, then once you have a son I’ll call you to sacrifice him, then for the grand finale at the last second I’ll stop you and say it was all just a test.

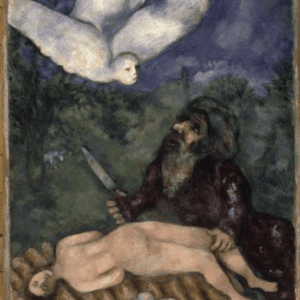

Marc Chagall, whose painting above depicts what is known in the Jewish tradition as the Akedah (Binding of Isaac) was the world’s preeminent European Jewish painter during the 20th century. The above painting of the Akedah, completed 1931, depicts the very end of the story in Gen 22, in which at the last moment after Abrahahm had “reached out his hand” the angel calls from heaven “Abraham, Abraham! Do not lay your hand on the boy.”

At first blush, this story could easily act as a witness to the fact that there may be times when the call to violence represents a supreme act of faith. As repugnant as it is to our sensibilities, among the Canaanite peoples, with whom Abraham is presently sojourning, child sacrifice was understood exactly in the way. The logic, as best as we can tell from history and archeology, was that the more important the object of sacrifice, the more devoted the person rendering it. Within the narrow confines of the binding of Isaac story itself, what we see is Abraham being tested based on his willingness to enact the redemptive violence of the culture around him.

Marc Chagall actually painted numerous different depictions of the Akedah during his career, but it is this second one, painted in 1966 after the full horrors of his people’s suffering within the Holocaust, which came to be regarded as among his true masterpieces.

Marc Chagall actually painted numerous different depictions of the Akedah during his career, but it is this second one, painted in 1966 after the full horrors of his people’s suffering within the Holocaust, which came to be regarded as among his true masterpieces.

In both paintings you have depicted Abraham, Isaac and the angel, in the foreground, with the background including the ram caught in a thicket (Gen 22: 13). Yet in his masterpiece, the post Holocaust version of the Akedah, Chagall incorporated scenes and images from history which significantly expand the capacity of the story to speak to the human experience, of the relationship between faith, redemption & violence.

Strikingly Chagall, a Jew, chose to include a depiction of the other only son, depicted in the Bible who, being deeply loved by his Father, must nevertheless bear the wood of his own sacrifice up a mountain.

In Genesis 22, Abraham’s summation of his experience that day on Mount Moriah is the cornerstone proclamation of faith, “the Lord will provide.”

But what exactly was provided?

The sacrifice needed for redemption (peace & prosperity), without inflicting violence.

It was Mark Twain who famously said that “a person who picks up a cat by the tail learns a thing he cannot learn by any other way.”

When considered with eyes of faith, Genesis 22, far from the depiction of a schizophrenic god’s last minute change of mind against filicide (killing of your own child), depicts a God desiring to fundamentally revolutionize the way humans seek redemption. Doing so in dramatic fashion, God invites Abraham to learn the dangers of playing with the “fires of Molech,” (see Leviticus 18:21) by calling him to reach out his hand towards it. In so doing he teaches Abraham, the father of faith, a thing about faith, redemption, and violence that he could not have learned any other way.

The great Abrahamic adventure is the call to a faith defined, not primarily by what we as humans are willing to sacrifice for the gods, but trust that what our God has sacrificed for us is enough to ensure the peace and prosperity (redemption) for which we long. The mechanism through which that lesson played out was a resounding “No!” to the sanctified violence of his surrounding culture.

And, where else might we find a society that, failing to trust the sacrifice made on its behalf, seeks to procure the peace and prosperity it desires, through redemptive violence? And who in that society are most often the ones that end up being sacrificed?

I wonder what so-called redemptive violence would the Angel of the Lord say “no!” to in our day?

In Hebrews 11 we are told that Abraham, the father of faith, believed that God could “raise Isaac from the dead.” It took eyes of faith (in the resurrection!) to reject the narrative of redemptive violence that surrounded Abraham. Once we, like Chagall and Abraham, allow Jesus to enter the picture, suddenly the masterpiece version of the story begins to come into focus, and we recognize that the cross is the LORD’s provision of nonviolent redemption which undermines every culture’s attempts to achieve it through their own violent means.