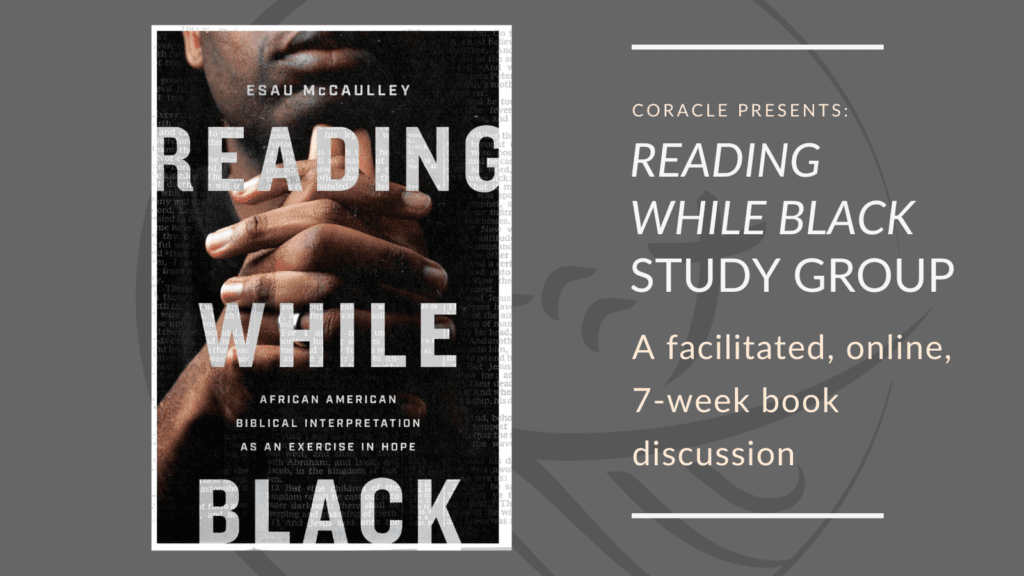

Over the course of the last 8 Wednesdays, a group of some 50 pilgrims and I have journeyed together through the award-winning book Reading While Black: African American Biblical Interpretation As an Exercise in Hope by an Anglican priest, the Rev. Dr. Esau McCaulley. The group of people was truly delightful, and the book was a profound gift around which to gather! If you haven’t gotten your hands on it yet (or have left it unread on your shelf too long, as I had), I strongly encourage you to read it (then read it again), ideally with other Christians who come from different racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and church backgrounds. I’m confident that McCaulley’s book will provoke you to think, to wonder, to pray, and to hope, just as it did for us.

How could one book provoke all that, you ask? Well, McCaulley’s book takes us deep into the Good Book which, he reminds us, has provoked, and continues to provoke, different people in many different ways. Just a few generations ago, Scripture provoked white slaveholders both to fear that their Black slaves would cry out to God for their own Exodus and to confidence that “slaves should submit to their masters.” During that same time, Scripture provoked Black folks to reject their dehumanization and to hope-filled struggle for liberation, both from slavery and from any other hindrance to following Jesus. McCaulley confronts the proverbial elephant in the room: How could people come to such different conclusions after reading the same Bible? And are different interpretations equally valid? Most importantly, what does God think about all this?

McCaulley reminds us that we all read Scripture from our social locations, bringing to it different questions and assumptions based on our cultural, socioeconomic, and personal backgrounds. To interpret Scripture, we all emphasize certain biblical texts over others, even if we (often!) do so unconsciously. And yet, not all emphases are faithful to the overall picture of God painted by the Bible. Slaveholders’ emphasis on “Slaves, obey your earthly masters” (Eph. 6:5), over texts like “Love your neighbor as yourself” (Lev. 19:18), and the Exodus narrative allowed them to dehumanize fellow bearers of God’s image. This grieves the heart of God.

McCaulley makes the case that the interpretive tradition of Black folks who saw right through slaveholders’ Christianity—the same tradition that’s been passed down through historic Black churches—is a singular gift to the Body of Christ. The bulk of his book embodies that very gift, showing how the Bible speaks to topics that are pressing to Black Christians today: policing, political engagement, the gift of ethnic particularity, and rage at past injustices—topics on which other communities might assume the Bible is basically silent. McCaulley’s insightful work in those chapters embodies his tradition’s “hermeneutic of trust” in which a community is “patient with the text in the belief that when interpreted properly it will bring a blessing and not a curse” (p.21).

Over the last 8 weeks, this group has not only gotten to witness McCaulley’s modeling of this patience with the text; we were also invited to model that patience together, with McCaulley’s text, with the Bible, and with one another. And it was beautiful. In a sociopolitical climate where mentioning the topics of “race” and “faith” alongside one another can provoke accusations of “politicization” and even “straying from the gospel,” it was a gift to experience a space of openness and blessing with Christians of different cultural and ethnic backgrounds. (If you’d like to experience a similar space centered on black experience, hosted by one of this group’s facilitators, sign up for Kitchen Table Conversations with Kathy!) As an Egyptian American who gets labeled as white, it was a gift to have my African-American-Middle-Eastern voice valued in its uniqueness, and I trust others felt equally seen and loved as well. I’ll conclude with one takeaway from the group: though we are bound to interpret the Bible in a way skewed by our backgrounds, that is neither a reason to despair nor to read the Bible “with a grain of salt.” Instead, it is an exhortation to deeply engage the Scriptures with people whose cultures and life experiences are “other” to us. If we make the effort of going beyond our relational and hermeneutical comfort zones, by God’s grace, we Christians may more truly be the salt of the earth. May it be so.