Jolts of inspiration don’t arrive in the mail every day.

But a while ago, my uncle called. He told me that in cleaning out his basement, he’d come across my great-grandmother’s Bible. He’d be happy to pass it on to me.

Nanny — as we affectionately knew her — fled poverty and near-famine in Sweden at the age of 12 in 1893, making her way with an older sister to settle in Chicago. I have only a few fuzzy memories of Nanny. She died at the age of 97 when I was 4.

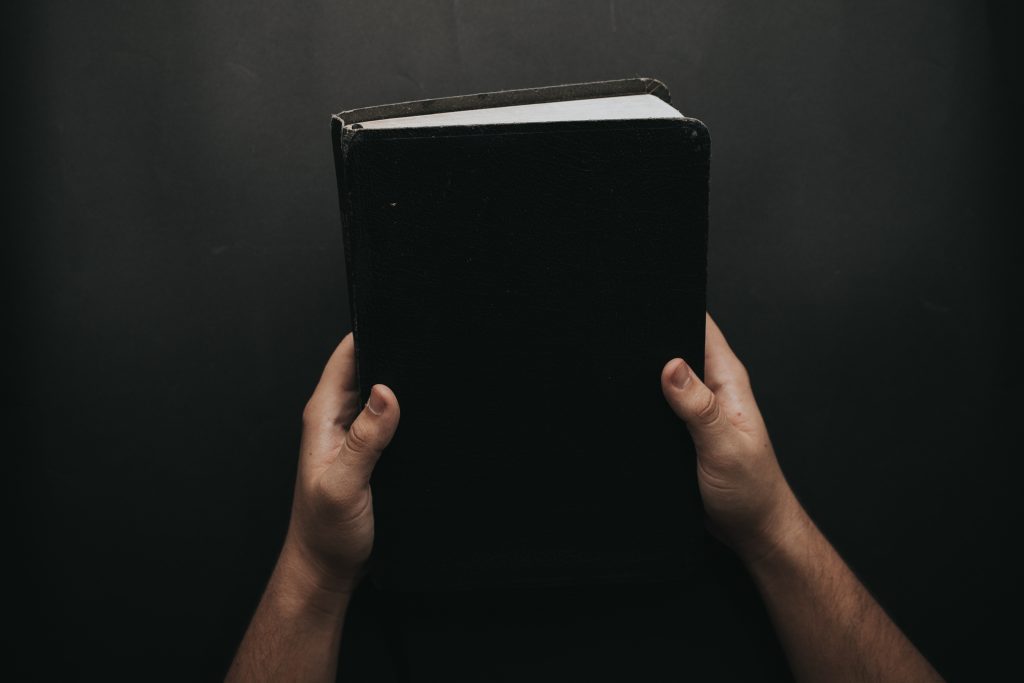

When the box arrived, I tore it open and gently opened her black leather King James New Testament and Psalms, which immediately released a universe of scents: leather, binding, aged paper and what can only be the trace that her hands left on every page. Nanny went through a succession of Bibles throughout her life, attending church every Sunday morning, Sunday evening and Wednesday evening, according to the Evangelical Protestant practice of the time. This was the Bible she had in her final decades and it would have been the one I tried to grab or drool on as a toddler crawling around her feet.

When the box arrived, I tore it open and gently opened her black leather King James New Testament and Psalms, which immediately released a universe of scents: leather, binding, aged paper and what can only be the trace that her hands left on every page. Nanny went through a succession of Bibles throughout her life, attending church every Sunday morning, Sunday evening and Wednesday evening, according to the Evangelical Protestant practice of the time. This was the Bible she had in her final decades and it would have been the one I tried to grab or drool on as a toddler crawling around her feet.

Over the decades, the cover’s black dye had given way beneath her fingers to reveal brown suede. The gold embossed letters “New Testament” nearly glowed. Some brittle pieces of tape secured the otherwise frayed binding.

I opened to the Psalms and the first page I saw had a passage underlined by Nanny’s pencil: “Now also when I am old and gray-headed, O God, forsake me not; until I have showed thy strength unto this generation, and thy power to everyone that is to come” (71:18). Immediately I sensed her affinity with this passage and her sense of humor in the almost playful, wavy line she made beneath “gray-headed.”

Nanny had strong, working hands that leap out of any family photo. The daughter of a bricklayer, she worked as a maid from the age of 15 in wealthy Chicago homes before eventually marrying and beginning her family with a steel mill worker and fellow immigrant. “Charge them that are rich in this world,” I found underlined in a passage that must have resonated with her, “that they be not high-minded, nor trust in uncertain riches” (II Tim. 6:17).

Nanny left no written memoirs, but as I became acquainted with my new treasure, I found that the pages of her Bible offered a record at least as intimate as any diary. The strokes of her pencil reveal her heart’s response to the revealed word of God. She seemed fond of the conversations between Christ and His disciples. Throughout the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles, she frequently underlined Mary, Priscilla, “mother,” or other women of scripture. The parables on servants and the mustard seed are heavily marked.

Absence — this from a woman who lost her father at the age of 10 and left her mother behind at 12 — is almost palpable: She drew a big “X” next to Colossians 2:5: “For though I be absent in the flesh, yet I am with you in the spirit.” Having lost her husband in her 50s, she traced large brackets around all the passages on widows.

As with the traces of any relationship, Nanny’s Bible holds secrets, connections known only to her and the object of her heart’s deepest affections. I found that she often underlined the word “love” with a bold, single stroke. Her hands wore the cover thin in a tender way. And as I turned the pages, a small yellowed piece of newspaper dated “March 12, 1912” fell to the floor. Whatever transpired on that date — a turning point in prayer, a moment of pain, or particular joy? — caused her to cut it out and keep it close to the spine of her Bible for the long decades to come.

Nanny’s Bible is far more than a sentimental heirloom. The witness of her Bible — its cover, its margins — poses questions for us today: What did this remarkable woman know which drew her to open the scriptures daily? What was revealed to her? What are we missing by allowing our own Bibles to collect dust?

Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI pointed to lectio divina — the diligent reading of scripture, accompanied by prayer — as that practice which “brings about that intimate dialogue in which the person reading hears God who is speaking, and in praying, responds to him with trusting openness of heart” (cf., “Dei Verbum,” No. 25). He added, “If it is effectively promoted, this practice will bring the church — I am convinced of it — a new spiritual springtime.”

I think Nanny would have agreed. Do we?

Johnson, a husband and father of five, leads evangelization efforts in the Arlington Diocese.